A sudden shift of momentum in a long conflict between industry and activists.

By Grant Hill – March 31, 2023

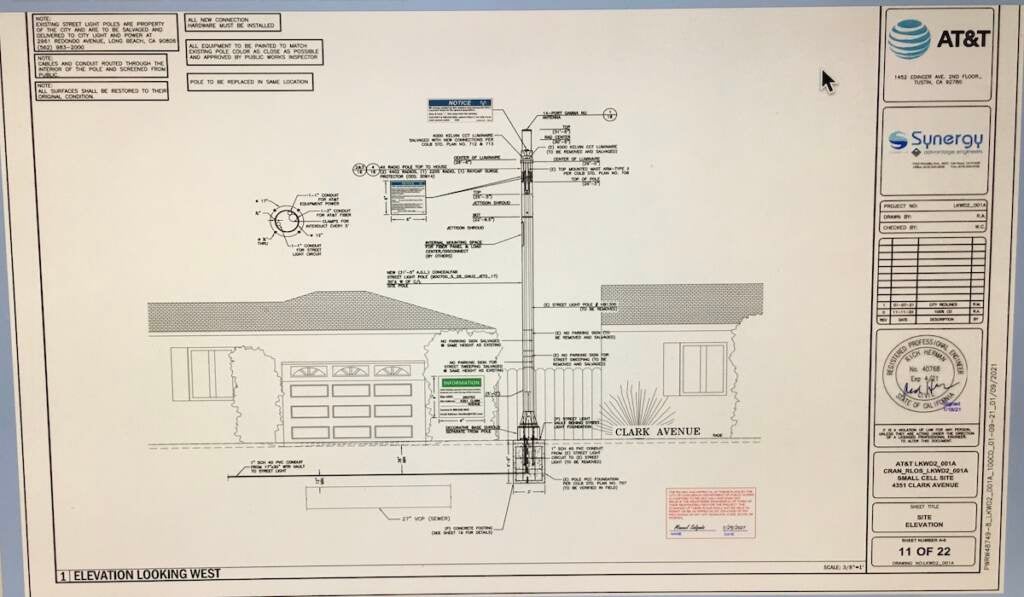

Moira Hahn and Mark Hotchkiss live in Long Beach, California, just near a streetlight that had been previously proposed for a 5G cell site. (Courtesy of Moira Hahn)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Moira Hahn and Mark Hotchkiss live in a small grayish ranch house in Long Beach, California.

It could easily be mistaken for others in the neighborhood if it weren’t for the front yard. It’s unusually lush; filled with bushes, palms, and a giant Australian pine tree.

There’s also this big metal pole — a street light more than 30 feet tall — right between the sidewalk and the street. It’s been there since Mark and Moira moved in over 20 years ago. They never thought about it much.

Then, in 2021, they received a letter from a company they had never heard of. It looked like junk mail, so it sat on the kitchen table for a couple of days unopened.

“When Mark opened it, he goes, ‘Why didn’t you open it?’” Hahn said. “‘You should read it.’ So, I read it. It’s like, holy mackerel, really?”

It was a notice informing them that the pole would soon be equipped with a wireless transmission facility – a WTF for short. All part of AT&T’s big 5G rollout in Long Beach.

“And it said, ‘Oh, by the way, there’s a sign on the lamp post,’” Hahn said.

She went outside to check and there it was. A simple flyer facing outward toward the street.

Since the 5G network was introduced nearly four years ago, countless others have received similar notices. More than 30 states have enacted legislation that makes it easier to install 5G cell sites like the one proposed for the pole in front of the Long Beach couple’s home.

Mobile markets research analyst Jason Leigh says the push boils down to three words: Internet of Things.

“You’re going to be able to connect more devices, more sensors, upwards of a million connections in a square mile — far and away what you can currently,” Leigh said.

According to Leigh, the 5G network is about much more than your cell phone connection. It’s about the connection of almost everything else: your car, your sprinklers, your toaster.

This newest generation of cellular technology is remarkably powerful and allows exponentially more gadgets to be connected, accessed, and controlled from almost anywhere.

“The networks themselves are the first foundational piece. And really what everybody’s trying to figure out is now what do we do with this?” Leigh said.

Just take Long Beach for example: The city is home to the second largest container port in North America and a crucial node in the global supply chain.

More than 2000 ships load and unload $200 billion worth of cargo there a year. Many of those vessels have sensors onboard that capture highly detailed, real-time information about weather conditions and traffic at sea. The data allows these ships to find faster routes and become more efficient.

With the help of 5G, the hope is to one day use that information to control entire fleets of unmanned ships from the shore. But the capabilities don’t stop there.

Imagine longshoremen wearing special shoes that track their gait as they work. The information collected could be beamed almost instantaneously to supervisors who can use it to help prevent injuries, or sold to third parties.

This is the promise, and potential peril, of 5G. A lot of money – and entire future business models – depend on a large, robust next-generation network.

But not everybody wants in. Moira Hahn and Mark Hotchkiss had 10 days to file an appeal against the permit for AT&T’s proposed 5G cell site on the pole in front of their home. The clock was ticking.

“When we got the notice, it didn’t bother me any,” Hotchkiss said. He is an electrical engineer who once hardwired their entire house for internet access before making the switch to Wi-Fi. So at first, he didn’t mind this technical upgrade right outside.

“But Moira was worried about what are the health effects of this,” he said.

Hahn had long suffered from serious migraines that forced her into retirement after years of teaching art at a nearby college.

In the days after they received the notice in the mail, she decided to consult her doctor about her migraines again. It was during that consultation that he suggested her migraines could be related to something called electromagnetic hypersensitivity, or EHS.

“My doctor started to say, ‘What about t Wi-Fi? You know, that could cause it. Try to get rid of all your cellular stuff, get rid of the walk around phones.’” Hahn said.

EHS is a little known, under-researched, and controversial health condition where people experience reactions to certain types of electromagnetic radiation, especially the kind that’s emitted by cell phone towers, or Wi-Fi.

Hahn looked it up online.

“There were quite a number of articles that said it’s not real or it’s psychological,” said Hahn. ”People experience symptoms, but it could be from something else.”

So the couple decided to run a test of their own. They returned to the old hard-wired system in the house and went back to using a corded phone. No more wireless internet or devices either.

Within a matter of hours, Hahn said her symptoms nearly disappeared. The migraines completely vanished after the electric company switched out the smart meter for an older model, she said.

But now, this proposed 5G cell site, just about 25 feet from the window where she painted, seemed to threaten her future wellbeing.

So the two rushed to file an appeal, and included a letter from Hahn’s doctor that explained her sensitivity to cell phone radiation.

She knew how it looked; the convenient timing of her diagnosis. But it didn’t matter to her.

“I didn’t care what people thought. I knew what I had experienced,” Hahn said. They found an attorney who could help them pro bono and soon their appeal was ready to file.

“I remember Mark and I rushing over to City Hall about 4 o’clock on a Friday to get it in by the deadline. And it was all locked up and [we were] banging on the glass until a security guard came and then being allowed in and getting a stamped receipt for it,” said Hahn. “And that’s when it all started.”

A city employee told Hahn not to get her hopes up. The way the city code was written, almost no one beats these things.

“He says, ‘I think only one person had ever beaten one of these, and she proved that she was in the historic district. And the code said that if it’s in a historic district, it can’t be erected. So she won,’” Hahn said.

What’s more, a prominent city council member also happened to be a registered lobbyist for one the largest communications infrastructure companies in the country – builders of cell sites just like the one proposed for their street light out front.

The couple was undeterred. As Hahn prepped for her appeal hearing, she kept researching.

“Tracking down experts, asking questions, seeing who we could get on as an expert witness, doing research, finding out what’s happening in other communities, what strategies did they use?” Hahn said.

She quickly discovered that the politics of cell phones, towers, and street poles extended way beyond city limits, and decades into the past.

Re-evaluating exposure limits

For many, the controversy kicked off with the passing of the Federal Telecommunications Act of 1996, when Congress sought to create a “seamless network of cellular communications” from sea to shining sea. That meant that while cities and towns could have a say in cell tower construction, they couldn’t flat out refuse to build them.

Many communities across the country were less than thrilled. By the end of the 1990s, more than 600 towns had placed moratoriums on building new towers, often citing fear of the unknown potential for long-term health effects of living near such cell sites. The New York Times described these efforts as “guerilla war.”A losing one.

As wireless communication exploded, the demand for high-speed internet became insatiable, and the number of towers in the U.S. ballooned. There are now more than four times as many as there were in 2000.

While activists continued the fight, arguing that uncertainty remains regarding potential health risks, industry has consistently reassured the public that federal guidelines – limits on exposure to radiofrequency radiation coming from these towers – protected people from harm.

Theodora Scarato disagrees.

“There [are] studies indicating harmful effects at levels below FCC limits,” Scarato said. “In other words, perfectly legal levels of exposure that are associated with harmful effects in research studies.”

Scarato is executive director of Environmental Health Trust, a non-profit think tank that’s been fighting the Federal Communications Commission over these health concerns for years. The FCC is not a health agency, but it is in charge of promulgating guidelines for safe cell phone radiation exposure – a determined threshold that’s currently based on studies done by the Navy in the 1980s.

“And the studies that … underpin how they came up with the level of what is safe, and what is not, are these small animal studies,” Scarato said.

Five monkeys and eight rats, to be exact. Researchers saw behavioral changes when the animals were exposed to high levels of radiofrequency radiation intense enough to heat their tissue — much like a microwave heats food.

So in 1996, when the FCC created the current guidelines for cell phone radiation exposure, the agency focused almost singularly on preventing these “thermal effects” in people, working under the assumption that exposure under those levels is otherwise benign.

But this was before cell phones had become ubiquitous. In 2013, the FCC opened a notice of inquiry inviting public comment to ultimately re-evaluate its guidelines based on new research.

“Meaning they asked these questions and invited comments from federal agencies as well as from the public and from experts and so forth. And they asked, should we change these limits? Are these limits adequate?” Scarato said.

This process went on for years as researchers and groups like Environmental Health Trust submitted new evidence that seemed to show cell phone radiation within the current limits could be related to all kinds of health issues.

“Headaches and cancer and oxidative stress … impacts to sperm and so forth,” Scarato said.

Among the work submitted was a 2018 study on cell phone radiation and cancer.

Researchers with the National Toxicology Program were tasked by the FDA to create the largest animal study on radiofrequency radiation ever using 90 rats and mice per exposure dose. It took 10 years and cost $30 million.

But Scarato, and researchers involved in the study, said federal health agencies dismissed the findings.

“The expectation was that since the FDA requested the information that they would get the information and they would run a risk assessment on this to determine what is an acceptable level of risk,” said Ron Melnick, a retired National Toxicology Program researcher who helped design the study. “However, they dismissed the NTP study even though they requested it.”

Ultimately, the FCC guidelines remained untouched.

For years, activists and researchers had accused the FCC of being “captured” by industry; a revolving door for telecom lobbyists at the federal level.

“They just ignored so much of what we had put on the record, and it seemed pretty clear that we could sue at that point related to their lack of adequate review of the record. So, we did,” Scarato said.

In 2019, Environmental Health Trust and others sued the FCC, seeking to force the agency to explain why they didn’t make a change to the guidelines. And remarkably, the group succeeded.

“The U.S. Court of Appeals, D.C. Circuit, determined that the FCC had acted in an arbitrary and capricious manner in their decision to maintain the limits,” Scarato said.

While a panel of judges found some of the agency’s reasoning satisfactory, like its response to research on cell phone radiation and cancer, the court mandated the FCC to go back and re-evaluate its guidelines based on research the agency had not adequately addressed.

The decision didn’t promise a change to the guidelines, only that the public would get a better explanation of the FCC’s final determination. The agency did not respond to recent questions about the status of that process.

Plenty of people and researchers maintain that the current guidelines are safe.

“There’s no reason to limit the use of whatever frequency in radio frequency spectrum as long as you keep exposure below the active guidelines. If you do that, then on the basis of what we know now — it’s safe.” said Eric van Rongen, Vice President of the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection, an independent non-profit organization that advises governments on radiofrequency radiation exposure limits.

Rongen contends that recent research showing health effects below the current FCC exposure limits often cherry-pick data and seek results that confirm pre-concieved hypotheses. While he admires the 2018 National Toxicolgy Program study, he disagrees with its conclusion.

“It’s very likely that they have been heated up by the exposure and that in some way the metabolism of the animals must change in order to get to maintain a proper temperature balance in the body,” said Rongen. “And the change in metabolism may have led to an increase in tumor for whatever reason.”

While Theodora Scarato and Environmental Health Trust question ICNIRP’s independence, U.S. health agencies also maintain that current exposure limits are safe.

Still, Environmental Health Trust’s big win against the FCC has provided new ammunition for those fighting towers and cell sites locally.

People like Moira Hahn and Mark Hotchkiss. By March of 2022, their neighbors in Long Beach had rallied around the cause — flooding the city with comments against the cell site proposed by AT&T. Nearly 50 people tuned into a virtual hearing for their appeal, including Theodora Scarato.

She wanted to speak in support of Hahn’s health concerns and discuss how her group’s win lended weight to those concerns.

The city’s outside counsel, Jeff Melching, called it legally irrelevant.

“We just follow the FCC’s rules. We understand what D.C. circuit’s decision meant for the need to change those rules going forward, but they haven’t changed yet,” said Melching. “I don’t want anyone on this call to think we are skeptics about the effect of [radiofrequency radiation] emissions, it’s just irrelevant.”

Eventually, there was a motion to vote on whether to deny the appeal. It was tie: 4-4.

The former infrastructure lobbyist on the city counsel recused himself. He’s since been elected mayor.

The potential cell site hung in legal limbo, with both sides unsure how to proceed.

But Doug Carstens, the lawyer who represented Hahn and Hotchkiss, was confident AT&T wouldn’t go down without a fight. He thought this was about something much bigger than this one 5G cell site on a lamp post; it was a matter of ceding ground.

“They don’t want to set the precedent of moving it to accommodate one person, because now they’re going to have to, they think, move it to accommodate everybody else or, you know, move it from here to over there and then move it again,” Carstens said.

Since the hearing, others in Long Beach have come forward against cell sites near their homes. Carstens believed the company feared a domino effect.

Meanwhile, both parties agreed to a temporary hold on a final decision, as the couple prepared for the worst. Hahn was so worried about the potential health effects, her migraines coming back, that they were getting ready to move.

“We put a lot of time and money into [getting ready to sell]. We ripped apart our house and had old heating removed and floors,” Hahn said.

The date the hold expired – March 1, 2023 – came with no word on a final decision. Another week passed. Still nothing.

Eventually, a representative at AT&T gave me the news: “Due to various reasons, we are no longer planning to build a small cell site at that location.”

The couple’s tactics seemed to have worked.

“We’re taking it with a grain of salt, knowing that it was a PR person talking to a reporter from where we heard it. So nothing’s official,” Hotchkiss told me.

A few days later, the city confirmed it: the battle was over. The big metal pole in front of their home would remain just a big metal pole. A street light.

And the all but inevitable future trespassing at their doorstep? Successfully shooed from the yard.

source : https://whyy.org/segments/california-couple-beat-future-at-their-doorstep-5g-cell-tower/

https://whyy.org/segments/california-couple-beat-future-at-their-doorstep-5g-cell-tower/