Crown corporation executive says most of the 1.9 million devices will last 20 years, as originally promised

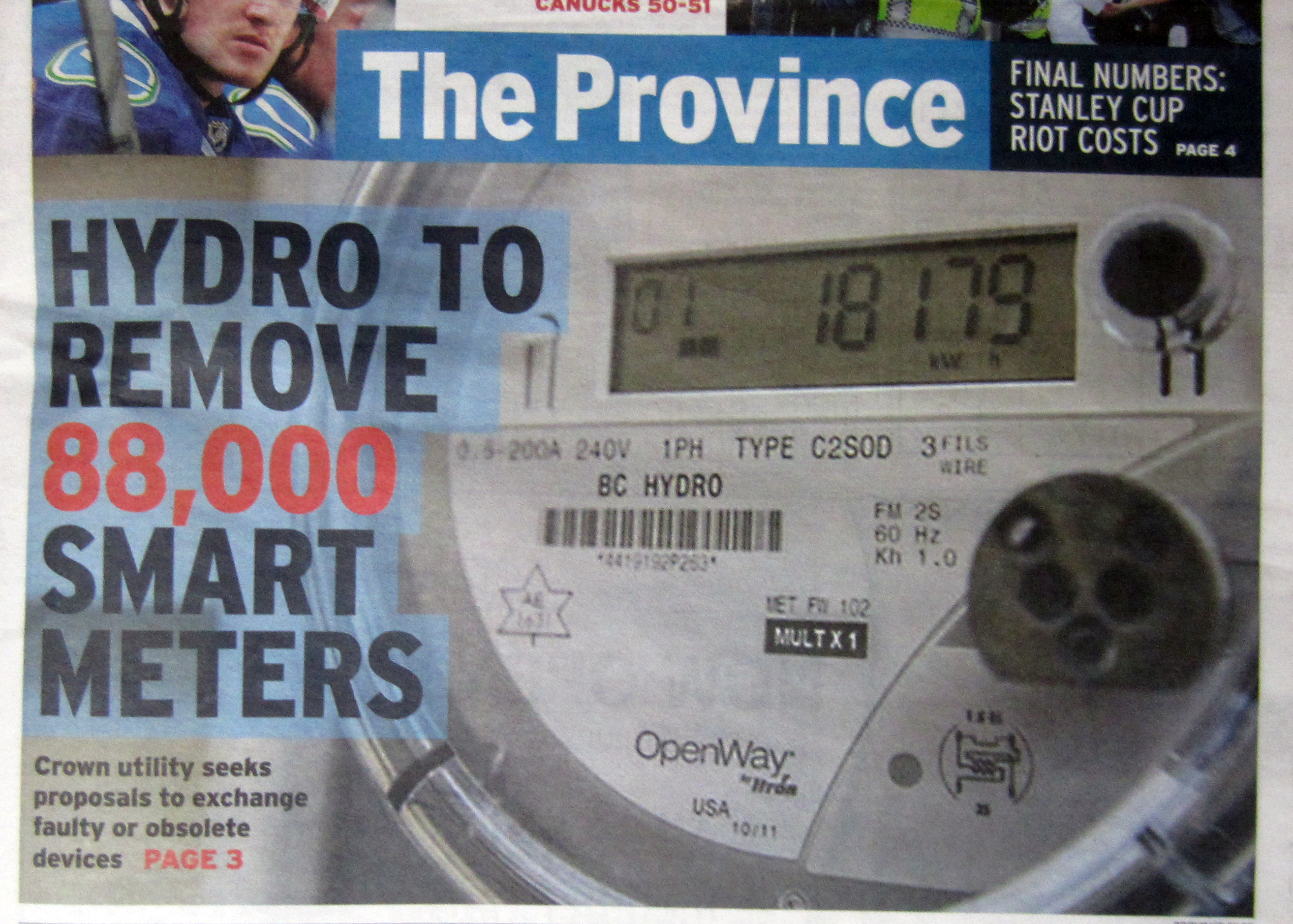

B.C. Hydro needs to remove more than 88,000 smart meters that are either faulty or may not meet Measurement Canada standards, public records show.

On top of that, the Crown corporation wants to replace 8,200 old analog meters and introduce nearly 5,000 new meters that work in rural areas that have poor wireless connections.

The total bill will be at least $20 million.

Despite this information — contained in a request for proposals to supply the new meters — B.C. Hydro’s vice-president of customer service Keith Anderson said he’s “confident” most of the province’s 1.9 million smart meters will last 20 years.

“We’re pretty confident at this point we’ll get the life expectancy we wanted and expected,” Anderson said.

B.C. Hydro estimates that by 2019 it will need to remove 40,000 faulty or failed meters, and another 48,000 meters for testing to see whether they still meet Measurement Canada’s accuracy standards. Hydro says those meters found to meet standards will be put back into its inventory.

The call for bidders closed Jan. 14.

New meters cost $200 each, including installation. Anderson said he was unable to release the budget for the replacement project and could not comment on the length of warranty for smart meters from supplier Itron.

“That’s commercially sensitive to Itron,” Anderson told The Province. “It’s something that we negotiated out past their regular warranty provisions.”

Under its old analog system, B.C. Hydro exchanged about 40,000 meters per year.

Doubts have been raised elsewhere in North America about the lifespan of smart meters. The 2014 annual report by the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario said “distribution companies we consulted said the 15-year estimate is overly optimistic,” compared to 40 years for an analog meter.

The report said smart meters are like other types of information technology: subject to upgrades, short warranties and malfunctions. Moreover, they will likely be obsolete by the time they are re-verified every six-to-10 years by Measurement Canada.

Last October, the chief information officer for Ohio-based FirstEnergy told a U.S. Congress subcommittee on power system security that the lifespan is five to seven years.

“These devices are now computers, and so they have to be maintained,” Bennett Gaines testified.

Anderson said he was not familiar enough to comment on either the Ontario report or that testimony, but said B.C. Hydro’s units are more advanced.

NDP critic Adrian Dix doubts both the 20-year life estimate and planned 20-year amortization period in the 2011 business plan. The project was budgeted at $930 million.

Dix said the number of failures would “presumably continue to go up as the smart meters get older.”

“Would you amortize your TV over 20 years? Would you amortize your cellphone over 20 years?” Dix said. “I don’t think you would. This is what B.C. Hydro has done or been ordered to do by the government.”

The tendering documents also show that the Crown corporation wants to replace 4,180 units by the end of March with ones that are cellular compatible. Those non-communicating units removed from rural areas and behind concrete walls will be returned to Hydro’s inventory,

Anderson said.

Health concerns motivate holdout

Liz Walker finds herself among a dwindling group of B.C. Hydro customers who refuse to convert from an analog meter to a smart meter.

“A lot of people folded because they couldn’t afford the legacy fees and they’ve been railroaded to accepting smart meters,” said Walker.

She pays $32.40 a month for her analog meter to be read manually at her house in Surrey and a property she inherited in Peachland.

B.C. Hydro installed 1.9 million smart meters from 2011 to 2013, but backed away in July 2013 from imposing smart meters on 68,000 holdouts.

Keith Anderson, Hydro’s vice-president of customer service, said there now are fewer than 14,000 customers paying extra to keep analog meters or use smart meters with the radios switched off.

A B.C. Hydro tender call seeking installation companies forecasts 8,200 “legacy-to-smart” exchanges in the next four years.

Walker said her original 1968 analog meter was replaced last summer with another analog one after the accuracy seal expired.

Walker, who said she worked as a chemical technician at B.C. Hydro’s Powertech Labs for 10 years until 1990, is concerned about health risks of radio frequency electromagnetic fields.

She said Hydro tried to convince her that the stucco walls at her Surrey house would reduce exposure levels. The problem was, Walker said, “my meter would end up behind that stucco wall” and too close for comfort to her son’s room.

In 2011, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classified radio frequency electromagnetic fields as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.”

A 2011 Health Canada document, however, says that exposure from smart meters does not pose a public health risk: “Survey results have shown that smart meters transmit data in short bursts, and when not transmitting data, the smart meter does not emit RF energy.”

Walker is hoping a B.C. Supreme Court class action lawsuit against B.C. Hydro gets a green light from the courts. Justice Elaine Adair reserved her decision Dec. 11. Smart meter foes want refunds and the choice to return smart meters for analog units.

“I don’t think, financially, the province can afford this program, especially if we’re going to replace smart meters within a decade,” Walker said.

— Bob Mackin

http://www.theprovince.com/health/hydro+must+remove+more+than+smart+meters/11660282/story.html